Updated 11 November 2021 with this comment…

Thank you for posting this article. I come to it yearly at Remembrance Day for my 2nd Great Uncle F/O David Griffin (maternal). This gives me an opportunity to share the well documented account of how he served and teach my daughter about our Canadian history. My family member located a copy of his book and has retained it in our family.

Research and story by Clarence Simonsen

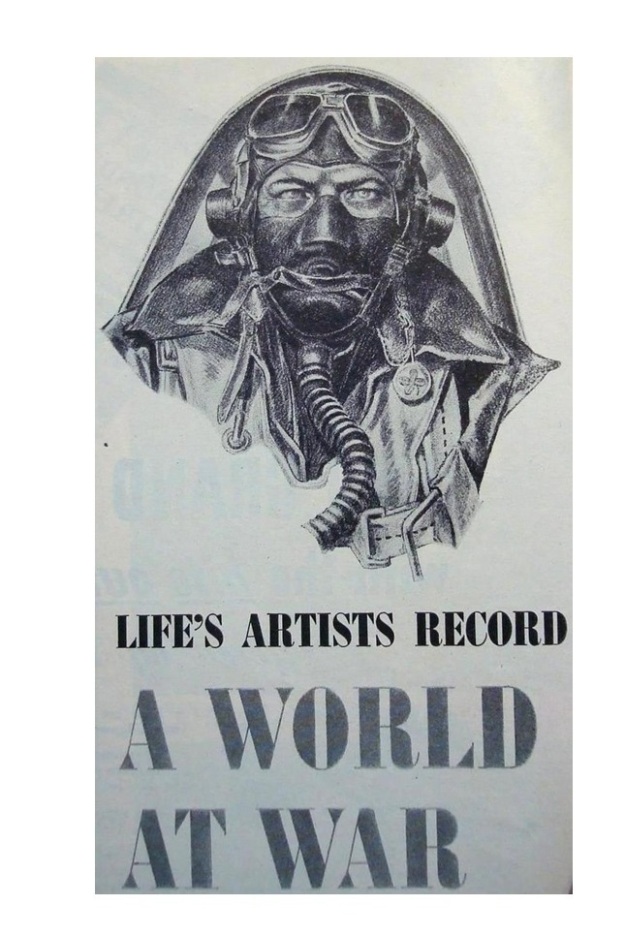

War correspondents are a special breed of men and women who continue today risking their own personal safety to capture a story, photo, or painting, and communicate the news back to the public. These people are neither soldiers of war or members of the armed forces. However they were given the same uniform and are treated with the same priority and respect as the fighting man and women. It is an exhausting, dirty, and deadly business, facing the sniper’s bullet and land mine which is impervious to the war correspondent badge. Near the end of World War Two [30 April 1945], LIFE magazine presented a portfolio on ten artists who had been in the conflict since December 1941.

My favorite American LIFE war correspondent artist was Capt. Tom Lea who wore the standard uniform of the United States Army Air Force. Only a small strip of cloth on his shoulders identified him as a war correspondent. Through the medium of pencil and paint Tom captured the mysteries, death, and spectacle of war art such as the American pilot expression and the four leaf clover he wore for good luck. His art appeared in many issues of LIFE magazine and dramatically showed how deep Americans had been plunged into the Second World War. It was the magic of the airplane and the U. S. Air Transport Command that flew Tom to the strange and new world at war.

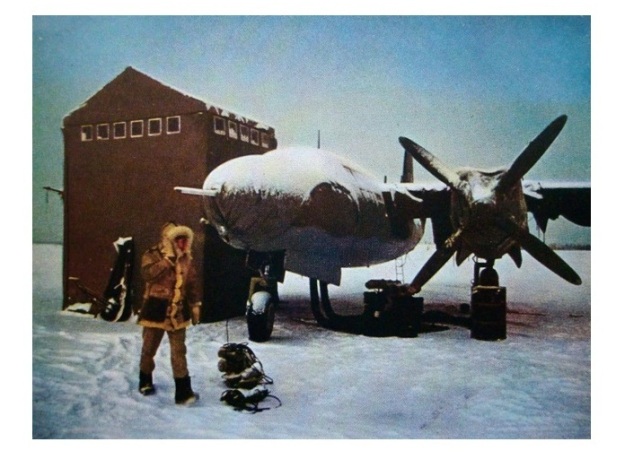

This image is from the 1944 book titled Flight to Everywhere by Ivan Dmitri, the story of the United States Air Transport Command in WWII.

The badge of the U.S. Army’s Air Transport Command contained the new boundary lines which changed the very shape of the world as these big transport aircraft flew the new circle routes. These routes opened up new remote landing strips and way stations for the aircraft to refuel and then depart on a network of bases from the Arctic to Australia.

By 1945, U. S. Air Transport Command flew regular plane routes that totaled over 160,000 miles. Artist Tom Lea, flew over 38,000 miles with Air Transport Command, including many trips around the world. He painted and brought back hundreds of images of the little-known places in the world, including Arctic Canada. When he stopped at Goose Bay, Labrador, in 1942, he painted images of the Arctic Northern Lights and the virgin forest that surrounded the remote air base.

He reported a Canadian, Eric Fry, found the base location while flying over the area in an amphibious aircraft in the spring of 1941. This was the only flat, sandy ledge, with room for runways and proximity to coastal waterways for thousands of miles. The base construction was a joint undertaking shared by both American and Canadian funds, containing both American and Canadian base camp areas. By 1943, the base could service and feed the crews of 100 aircraft in just 24 hours. Then weather permitting, they continued the Great Circle route to Greenland, England, and the war in Europe.

This Tom Lea painting records one of the thousand rivers that cross the plateau near the great base of Goose Bay airport. This was recorded as being near the 300 foot Hamilton waterfall where the Indian spirit Manitou, lives.

The next day Tom painted the enormous piece of Danish ice covering 700,000 miles of frozen island Greenland.

Many American airmen in Goose Bay came from the southern states. They were not prepared for the cold Arctic life style and from this was born the legend of the “Kee-kee Bird.”

The Kee-kee Bird

This bird looks just like a buzzard;

It’s large, it’s hideous, it’s bold.

In the night, it circles the North Pole.

Crying “Kee, Kee, Kee-rist but it’s cold!”

Images taken in December 1943, from book “Flight to Everywhere.”

Goose Bay, Labrador, Canada became the hub for the hundreds of American war correspondents traveling to the war in Europe and many of these men and women never returned to the United States.

On 20 September 1948, at 5 p.m. American Secretary of Defense James Forrestal dedicated a special memorial wall honoring the 80 plus American war correspondents who died or were killed during their war service. The wall was located in the National Military establishment Press room, [2E 676] of the Pentagon building. On any given day, forty war correspondents photographs will be mounted on the memorial wall, giving the location and date of death or missing in action.

In 1945, Gillis Purcell and Ross Munro formed the Canadian War Correspondents Association, which today records and represents over 100 Canadian reporters who served and died scattered all over the world. Two Canadian War Correspondents from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Art Holmes and Robert Bowman, departed Halifax, Nova Scotia, in a convoy for England in late December 1939. They would spend the duration of the war wearing the standard Canadian Army attire which was identical to the front line soldiers they served beside in action.

Other Canadian newspapermen served as civilian war correspondents, while many served as members of the armed services in the public relations sector. Several didn’t come home. To their roll of honor, you can add the name of RCAF Flying Officer David Francis Griffin # C24863.

David Griffin was born in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1907, and began his newspaper career at age seventeen, working as a press boy for the Hamilton Spectator.

He moved on to become a newspaper reporter and was employed with the Windsor Star, Sudbury Star, and became assistant city editor of the Toronto Star newspaper. He was a widely-known and very well respected newspaperman with 18 years’ service when he enlisted in the RCAF in late 1941.

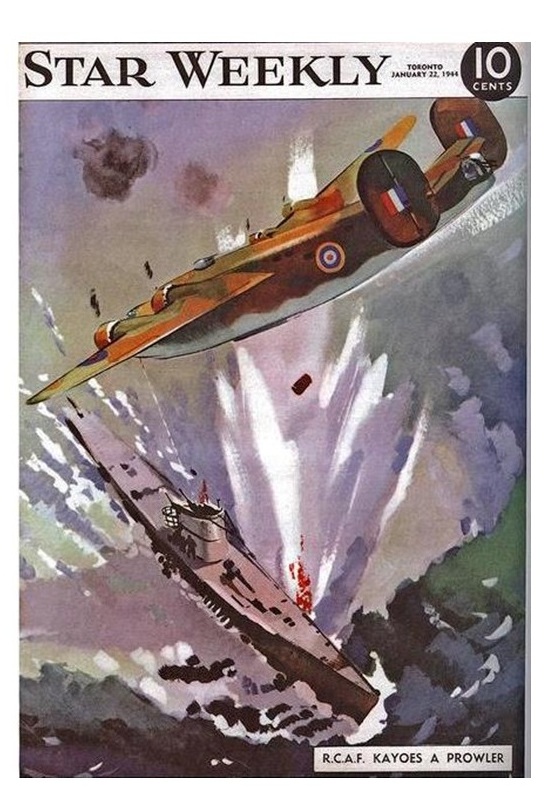

The sudden crippling attack by Japan on the United States naval and air forces at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, quickly changed the war defenses in Canada and Alaska. F/O Griffin was assigned to cover this air defence of British Columbia and Alaska, attached to the new formed No. 111 [Thunderbird] Squadron. Some of his RCAF reporting would appear in his old newspaper the “Toronto Star” including the special color center-section titled “Star Weekly.”

By May 1942, the tide of war was running very strongly in favour of Japan, and the U.S. War Department had to immediately booster its Alaska Air defence and ask if Canada could led air assistance to the American Forces in Alaska. On 27 May 42, Maj./Gen. S.B. Buckner, commanding the Alaska Defence Command, sent an urgent message requesting one RCAF Bomber Squadron and one RCAF fighter Squadron to proceed at once to Yakutat at the north end of the Alaska panhandle. On 2 June 42, twelve Bolingbroke bombers of No. 8 [B.R.] Squadron RCAF left Patrica Bay, B.C., for the 1,000 mile flight north to Yakutat, where they all arrived the next day. On 4 June No. 111 [F] Squadron under command of S/L A. D. Nesbitt arrived at Yakutat. The RCAF ground crews arrived by old Stranraer aircraft on 2 June and one of the passengers was F/O David Griffin. Lorne Bruce of Vancouver, B.C. the former superintendent of the Canadian Press at Edmonton, Alberta, was also selected to cover the RCAF in the Aleutians.

S/L Nesbitt joined the RCAF on 15 September 1939, then served with No. 1 Squadron in the Battle of Britain. Nesbitt returned to Ottawa on 18 September 1941, and took command of the new formed No. 111 Squadron on 1 November 1941. After the attack by Japan at Pearl Harbor, No. 111 Squadron was ordered to Sea Island, [Vancouver] B.C. on 14 December 1941. On 18 February 1942, they were moved to Patricia Bay, where they completed training in the new Kittyhawk Mk. I fighter aircraft, becoming operational on 12 March 1942. During this time period, public relations officer F/O David Griffin was attached to No. 111 Squadron and recorded all the squadron activities until August 1943.

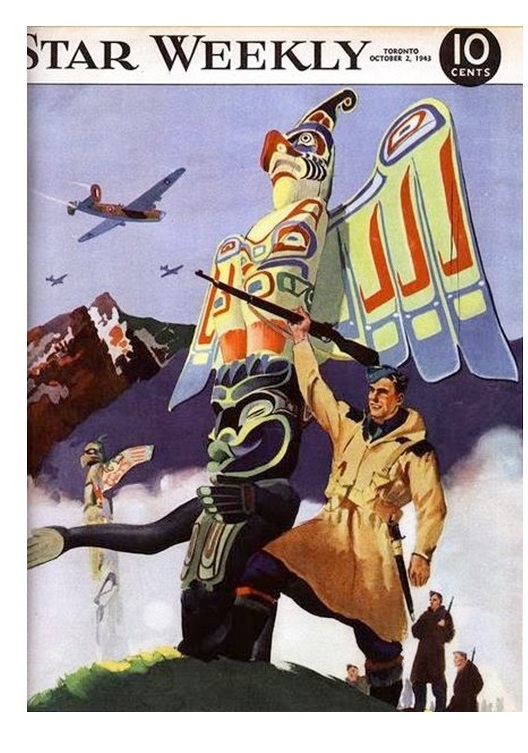

On 17 March 42, a special ceremony was held when the West Coast Saanich Indians adopted the fighter squadron and presented S/L Nesbitt with a 20 inch carved and painted “Thunderbird” totem pole. This was reported by F/O Griffin and images appeared in the Star Weekly magazine.

17 March 1942, S/L Nesbitt, D.F.C. and his Thunderbird. Star Weekly image

On 15 June 42, Nesbitt was promoted to Wing Commander and given command of RCAF Station Annette Island. The little “Thunderbird” totem stood on his desk for all to see.

Ottawa image PMR 75-603

No. 111 flew their first operation on 1 July 1942, from Elmendorf Field, to intercept an unidentified aircraft. A few of the fighter aircraft painted the Thunderbird totem as nose art, as seen in the recovery image of Kittyhawk Mk. I, serial RAF AL194, [RCAF #1087].

The RCAF No. 111 Squadron formed “F” flight of the 11th Pursuit Squadron commanded by Major John S. Chennault, the son of the famous Major Gen. Claire Chennault of the Flying Tigers fame.

In a few days motion picture producer Col. D. F. Zanuck arrived and shot color flying scenes of the war in Alaska. This film can be downloaded and watched today, including the unrehearsed scenes of the RCAF “Thunderbird” squadron.

In 1943, the U. S. Navy commissioned war correspondent artist Lt. William F. Draper to capture the war in Alaska. These two of 42 paintings, record the conditions at Umnak Island where the RCAF No. 111 Squadron were based.

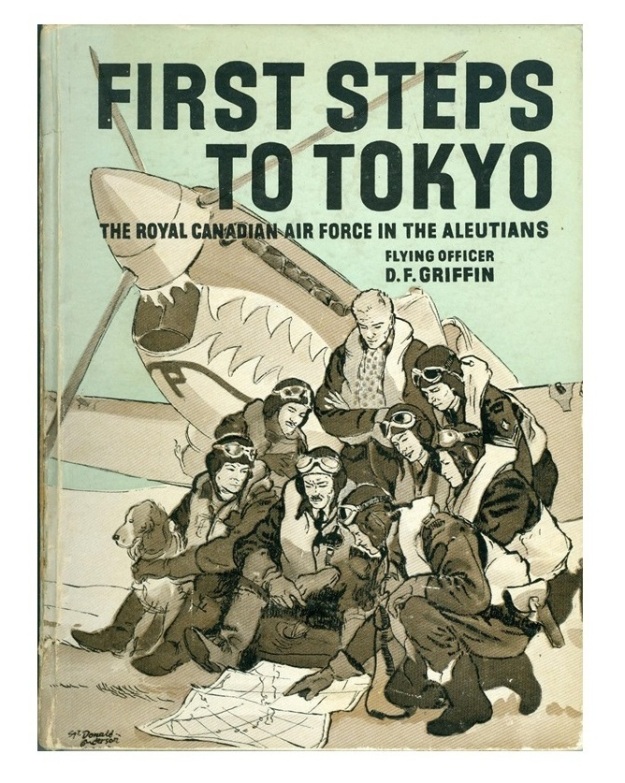

Public Relations Officer F/O David Griffin was attached to No. 111 Squadron from March 1942 until August 1943, completing two tours of operations against the Japanese forces. During this time he recorded the interesting account of RCAF operations and of the life involving the Canadians who served in the Aleutians. His unpublished manuscript was titled – “First Steps To Tokyo.”

After taking thirty days leave, he was assigned to cover the story of the Norwegian patrol bombers flying from Iceland, protecting the Atlantic convoy ships from German U-boat attacks.

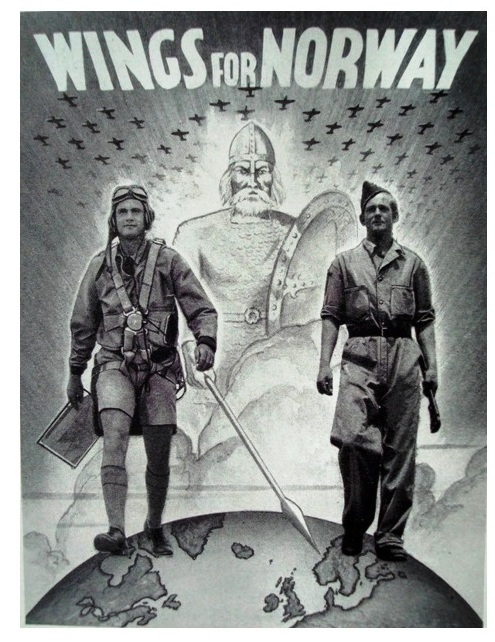

Images from the 1945 book “Little Norway” Publisher unknown

When Hitler suddenly attacked Norway on 9 April 1940, the Norwegian Government fled to Canada and purchased 20 million dollars of American combat aircraft. The first training of the Royal Norwegian Air Force began 10 November 1940, next to the Toronto “Maple Leaf” baseball stadium which was now named “Little Norway.” Fairchild trainers, Curtiss fighters, Douglas attack bombers and new Northrop patrol bombers were now seen on the Toronto Island Airport, which had been obtained for use from the Toronto Harbour Commission. By 1942, the Canada trained Norwegian fighter squadrons were taking the fight to Hitler, and this included Catalina flying boats and new Northrop N3-PB patrol bombers flying from Iceland bases.

The training in the N3-PB float aircraft at Toronto Island Airport, “Little Norway” July 1941

Wings parade at Toronto Island Airport, “Little Norway” 1941

LIFE magazine 29 May 1944

Bernt Balchen sketch by war correspondent Tom Lea in Iceland, 1943. He learned to ski at age eight and flew in the Norwegian Naval Air Force. He piloted Admiral Byrd to the South Pole 1927, then became an American citizen in 1931. In 1940, he assisted the Norwegian Government to begin pilot training at “Little Norway” in Toronto. In 1941, he was placed in command of the northern U.S. air base at Goose Bay, Labrador, and the main base in Greenland. All his life he was involved with snow, ice, and aviation.

In February 1944, F/O Griffin completed his story on the Royal Norwegian Air Force in Iceland, but his story would never be published.

Reykjavik, Iceland, was the H.Q. for No. 330 [N] Royal Norwegian Air Force and a major base for the RCAF Liberator bombers that were hunting German U-Boats. No. 10 [Dumbo] Squadron of the RCAF used this as refueling base on flights from Gander, Newfoundland.

On 18 February 1944, F/O Griffin secured a ride in a No. 10 [Dumbo] Squadron Liberator GR. V 856 bomber returning to its base at Gander, Newfoundland, from Iceland. This B-24 had delivered ground personnel from No. 162 [B.R.] Squadron to Reykjavik, Iceland, and was returning home empty with crew of five.

No. 10 [Bomber] Squadron had been formed at Halifax, Nova Scotia, 5 September 1939, and established a record of 22 attacks on German submarines, with three confirmed sinking’s. They were also proud to have two unofficial titles “North Atlantic” and “Dumbo” Squadron. Walt Disney artists in Burbank, California, created the unofficial insignia. They had moved to Gander, Newfoundland, on 8 May 1943 and continued anti-submarine duty until disbanded on 15 August 1945.

F/O Griffin would be the only passenger in Liberator [U.S. #42-40526] RCAF serial 586, the very first bomber assigned to the squadron on 15 April 1943. This bomber had scored the units very first U-Boat kill 15 September 1943, when it sunk U-341. This should have been a safe normal flight but freezing temperatures caused icing problems. Three inches of ice built up under the wings and this cause the aircraft to consume more than normal fuel for the flight. The last contact with the crew was when they acknowledged a signal to divert to Goose Bay, Labrador. The story of this crash first appeared on 5 January 1945, in the British magazine “The Aeroplane” titled – Crash in Labrador. It can be found online, but in short the ice covered bomber ran out of fuel in three engines, and then just thirteen miles from Goose Bay, the fourth over-stressed engine caught fire. The Liberator plunged headlong into the thick bush and struck many large eighteen inch diameter trees, snapping the bomber fuselage in half. F/O Griffin was thrown out and killed instantly. The other five crew members all survived.

In the fall of 1944, the RCAF published the manuscript of Flying Officer David Griffin, titled First Steps To Tokyo. The front covers were designed by another RCAF famous Official War Artist, Donald Kenneth Anderson. In the early 1990s, I had the pleasure to meet this artist at a dinner in Nanton, Alberta. It is possible this original art survives today in Anderson’s War Museum collection in Ottawa.

It is also possible that F/O David Griffin and RCAF artist Sgt. Donald Anderson knew each other. Anderson had painted covers for the Star Weekly magazine as early as 1940, and Griffin was then employed as assistance city editor for the Toronto Star.

Booklet here

War correspondent artist Tom Lea drawing of Gen. Claire Chennault, China 1943.

[LIFE magazine 29 May 1944]

F/O David Francis GRIFFIN C24863 is buried in the Goose Bay Cemetery, Goose Bay, Labrador, Canada.

The war correspondent from Canada and the United States represent a free press, for the free people, and they are not afraid to die for both. In the United States the newspapermen and women killed as a direct result of their chosen war correspondent assignment are remembered in memorial walls, arches, and special televised dedication by the Overseas Press Club.

In Canada, we forget about our Newspaper Heroes, but they are there, being killed in a far off dirty land just to bring us a story to read with our morning coffee.

On 30 December 2009, a young 34 year old Calgary Herald reporter was on a six-week assignment as a war correspondent in the War in Afghanistan. She wore the same uniform as the four Canadian soldiers that carried out a route patrol in an armoured military vehicle. They struck a roadside bomb and all five were killed together in the blast.

This World War Two story is dedicated to Canadian War Correspondent Michelle Justine Lang, 31 January 1975 – 30 December 2009. The first Canadian journalist to die in the war in Afghanistan, but never forgotten.

Calgary Herald image

Copyright Clarence Simonsen 2016

Reblogged this on Lest We Forget II and commented:

Research and story by Clarence Simonsen

LikeLike

More interesting information here…

http://www.rcaf111fsquadron.com/sources.html

LikeLike

Indeed they are a rare breed. To step into a war zone and report on what you see takes a huge amount of guts!

LikeLike

I feel priviledged to have Clarence trusting me to post his research.

LikeLike

Thank you for posting this article. I come to it yearly at Remembrance Day for my 2nd Great Uncle F/O David Griffin (maternal). This gives me an opportunity to share the well documented account of how he served and teach my daughter about our Canadian history. My family member located a copy of his book and has retained it in our family.

LikeLike

The original post is here…

LikeLike